I’ve been sort of abstractly thinking about lies, lately — because we’re in an age of rampant disinformation and active contempt for even the most hard-won authority, and because I’ve been reflecting on my personal relationships, including ones that have ended with people who had a (let’s say) creative relationship to the truth.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the lots of times I’ve said something and not been believed, not necessarily because I’m not trustworthy or don’t have a good reputation, but because the person or people challenging my appeal for the truth were louder, more willing to cross other people’s boundaries, could live with getting what they wanted by being manipulative or using emotional blackmail, had financial or cultural capital power to wield against me, and/or had the most people listening. I’ve also been thinking about how there are lots of ways to say things that aren’t true which are not lying in the strictest sense, and how the moral weight of right and wrong, practical questions about who is trustworthy or not, can become very muddled and confusing.

I don’t like it when people lie to me! I would say it’s among the nonviolent interpersonal behaviours I dislike the most, and I think that this is reasonable and practical, and has to do with the fact that lying undermines the primary assumption that underwrites most communication. It’s literally impossible to speak, and be understood, if we can’t generally assume people are telling the truth. The fact that most people tell the truth most of the time is the only reason it’s even possible to get away with telling a lie. People tend to reflexively reject people they catch lying, less because lying is uniquely bad, morally speaking, and more because their presence in a social environment undermines the foundation of communication.

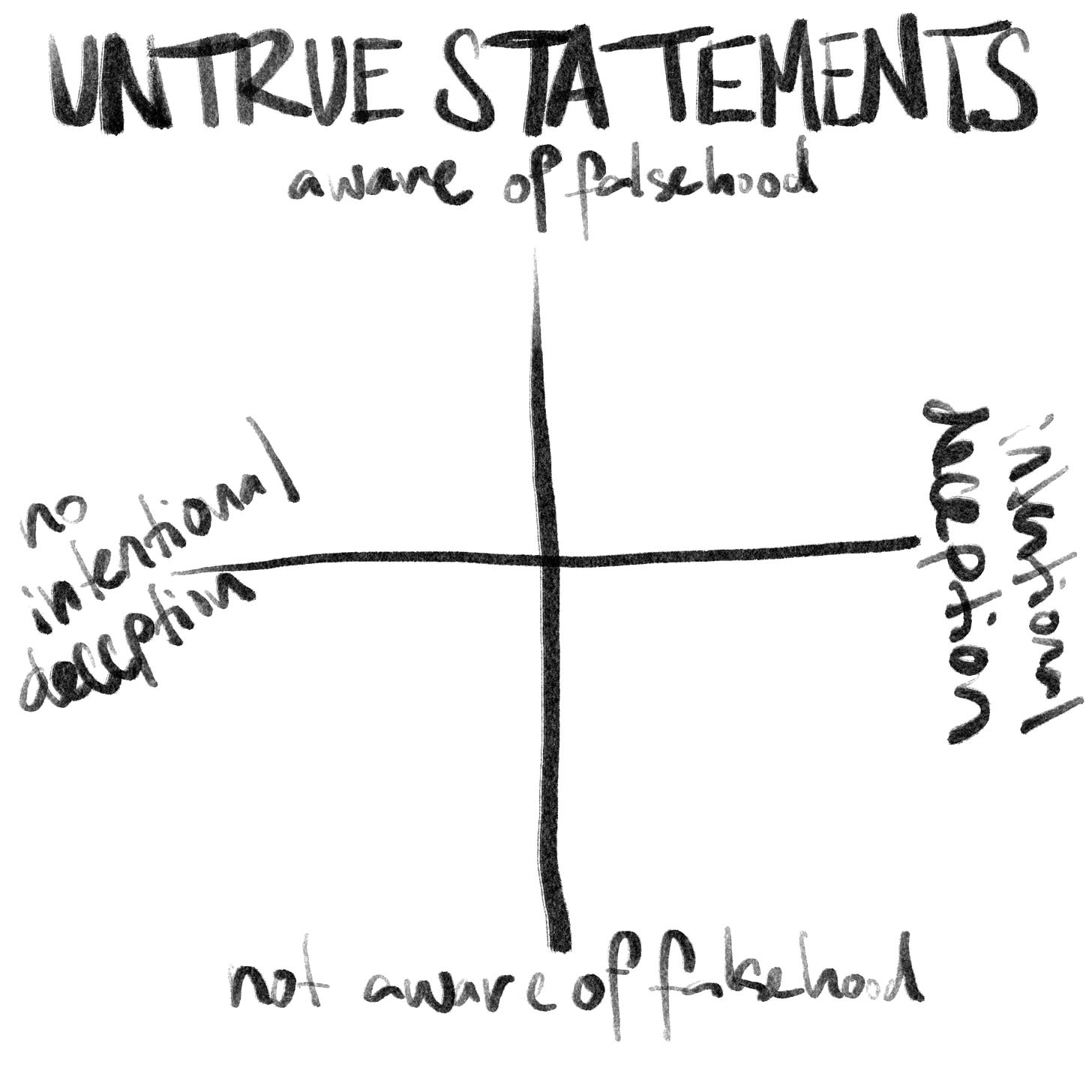

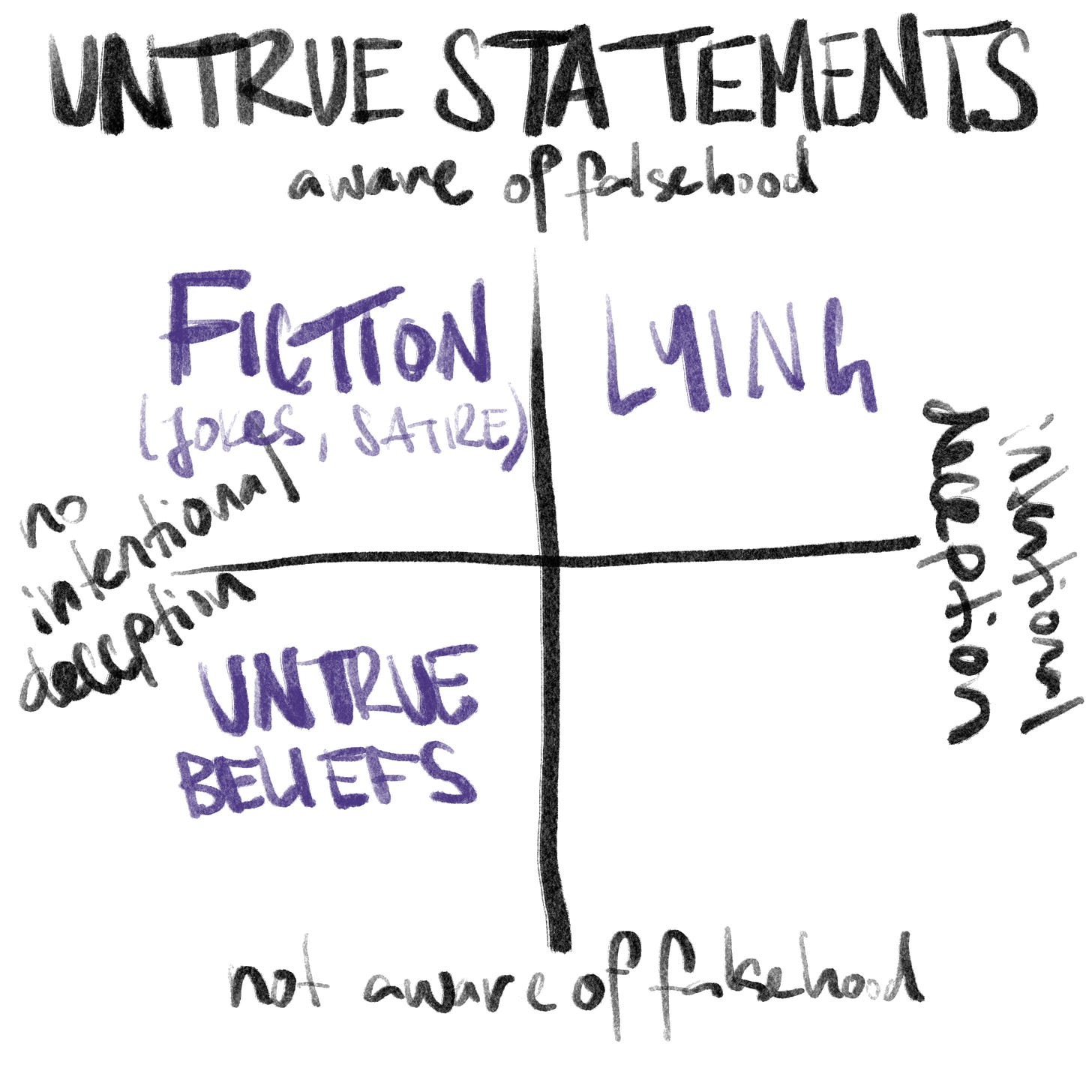

An intentional lie is only one example of someone saying something that isn’t true. There are lots of reasons people might do that. While I was out for a dog walk today, I envisioned a little graph that looked like this:

Because it seems very intuitively true to me that a lie proper requires both the intention to deceive and the knowledge that what’s being said is not true. That would put lying in this part of the graph:

But one of the most common examples of someone saying shit that’s not true that’s just whatever, and not really morally blameworthy at all, is if they have no intention to deceive, specifically because they have no knowledge that what they’re saying isn’t true — because they are making statements that come from beliefs they came by honestly, but are also false. We can call these “untrue beliefs.”

To make a very stupid example of myself, in high school I spent literally multiple years believing that rabbits had two uteruses. In my mind, I had this on good authority (I remembered a super smart friend told me this! She was never wrong about science stuff!) and I had never looked it up. I repeated this with great confidence to several people, several of which believed me, before I found out it wasn’t true — and then, later, read a journal entry in which I’d recorded a dream where my smart science friend told it to me. Somewhere along the line, I’d remembered the very vivid dream as a thing that actually happened, forgotten the fact that it was a dream, and with totally good intentions had repeated it as fact to several people. This was not a lie, it was me repeating something I genuinely believed, about which I was also incorrect.

There are obviously degrees to this. One of the problems with saying things that are not true is that it undermines your authority, or even trustworthiness. A sixteen year-old repeating something she assumes is true because she has some shadowy memory of a trustworthy person saying it is very developmentally normal for a sixteen year-old. If I did the same thing now, as a 32 year-old, this might be less adorable, or even lead people to be like, hey it’s annoying that you didn’t google that. If I took on some kind of paid educational role in which I repeat very google-searchable falsehoods, I would perhaps be even more blameworthy. If I lead children or vulnerable people astray with my misinformation, we have perhaps moved into the territory of negligence causing harm, for which it might be reasonable to remove me from my teaching position, for not living up to the responsibilities conferred along with the rights and benefits of a position of authority. And if I shout down, denigrate, or otherwise argue with an actual expert, about stuff I erroneously believe to be true, and have never confirmed, I might very well be guilty of a dangerous kind of hubris in addition to not knowing what I’m talking about.

People might also hold untrue beliefs even with access to the truth, because they erroneously believe that the evidence informing their untrue belief is more robust than the evidence disproving it, or because they are dissociatively attached to the associated scaffolding of their untrue belief — dismantling it would destabilize their worldview, in a way that feels too threatening to examine.

If the issue at stake is a matter of opinion, or is otherwise part of a more plastic appeal to epistemic authority, then that’s something different — when I say that people sometimes say things that are not true because they have beliefs about the world that are false, I’m not talking about the kind of “being wrong” that insists, for example, that totally free-market capitalism generates more liberty than socialism, which is an understandable perspective to have even if I personally don’t think it’s true. I’m talking about the kind of “being wrong” that causes someone to drunkenly yell at me at a party that Joni Mitchell totally played at Woodstock, and that’s why she wrote the song “Woodstock,” because that’s something their uncle who knew a lot about music told them when they were thirteen and they never bothered to check if he was right or not. It’s not true, and it’s annoying, but also there is a level on which like, who cares — everybody makes mistakes, and while it’s annoying, I don’t think it’s morally wrong unless this person was like, also being paid by a reputable university to teach a course about musicians who played at Woodstock. Even then, it’s kind of dumb and irresponsible, but it’s not, like, evil. If someone thinks that person was lying about this thing to commit a deception on purpose, I think that’s a mistake.

I also might say something that is not true with no intention to deceive anyone — like telling a joke, or writing fiction or satire I genuinely believe no reasonable person could possibly take as the truth.

In this situation, I might be wrong about that “no reasonable person” assumption — I think about the War of the Worlds radio play, or how telling any joke at all on the internet seems to inevitably attract the one guy who not only did not understand the hoke, but who also finds any instance of not knowing what’s going on psychologically unbearable, and so genuinely thinks that their not understanding a joke means that the jokes is bad, or even (and people have told me this!) morally wrong. When I was in college, there was a social justice orthodoxy maxim that intention has no bearing on the moral quality of a statement or action, that it literally doesn’t matter if, for example, I had no idea that the YA book I wrote would inspire a very strange person to murder John Lennon, because how could I possibly — what’s important is that it did, and I need to accept responsibility as if that was always what I set out to do.

I can see how having a hard-line, effects-only way of assessing the consequences of something cuts through a lot of the bullshit that comes along with making amends or getting an apology from someone, and obviously “it was a joke” or “I didn’t mean it that way” or “this was all a huge social experiment” are common bad-faith refrains echoed by people who did some shit on purpose, or at least in a very stupid and reckless way, and now want to recuse themselves from consequence. But I’ve never thought it was reasonable to hold someone accountable only ever for the effects of what they’ve done, with no space for intent. I think this enables an emotional blackmail-y kind of strong arm-ing, the idea that my being the most upset in a conflict automatically necessitates restorative action on the part of the person who upset me, instead of my letting it go because I misunderstood. I think it’s an essential part of becoming a good, functional person to learn to laugh it off when I look foolish, to not take myself or my perception of things too seriously.

In the law, when somebody causes the death of another, we have a distinction between an accident, negligence causing death, and murder, because we have an understanding that a horrible and tragic mistake is different from reckless behaviour that causes death, which is different than a person of sound mind killing another person on purpose. Saying something that’s not true, with no intention to deceive anyone, and accidentally causing a misunderstanding is obviously, to me, very different from lying, even if the effects of this end up being serious. There is really only so much control I have over other people misunderstanding me.

I have a hard time imagining what it would mean to say something that I am not aware is not true, where I also have the intention to deceive, except maybe a failed lie — in this case, there are hopefully no meaningful consequences to my lie except that I prove myself to be someone who at least makes attempts towards lying, which makes me untrustworthy. This seems like a stupid example, though. If anyone has better suggestions please tell me.

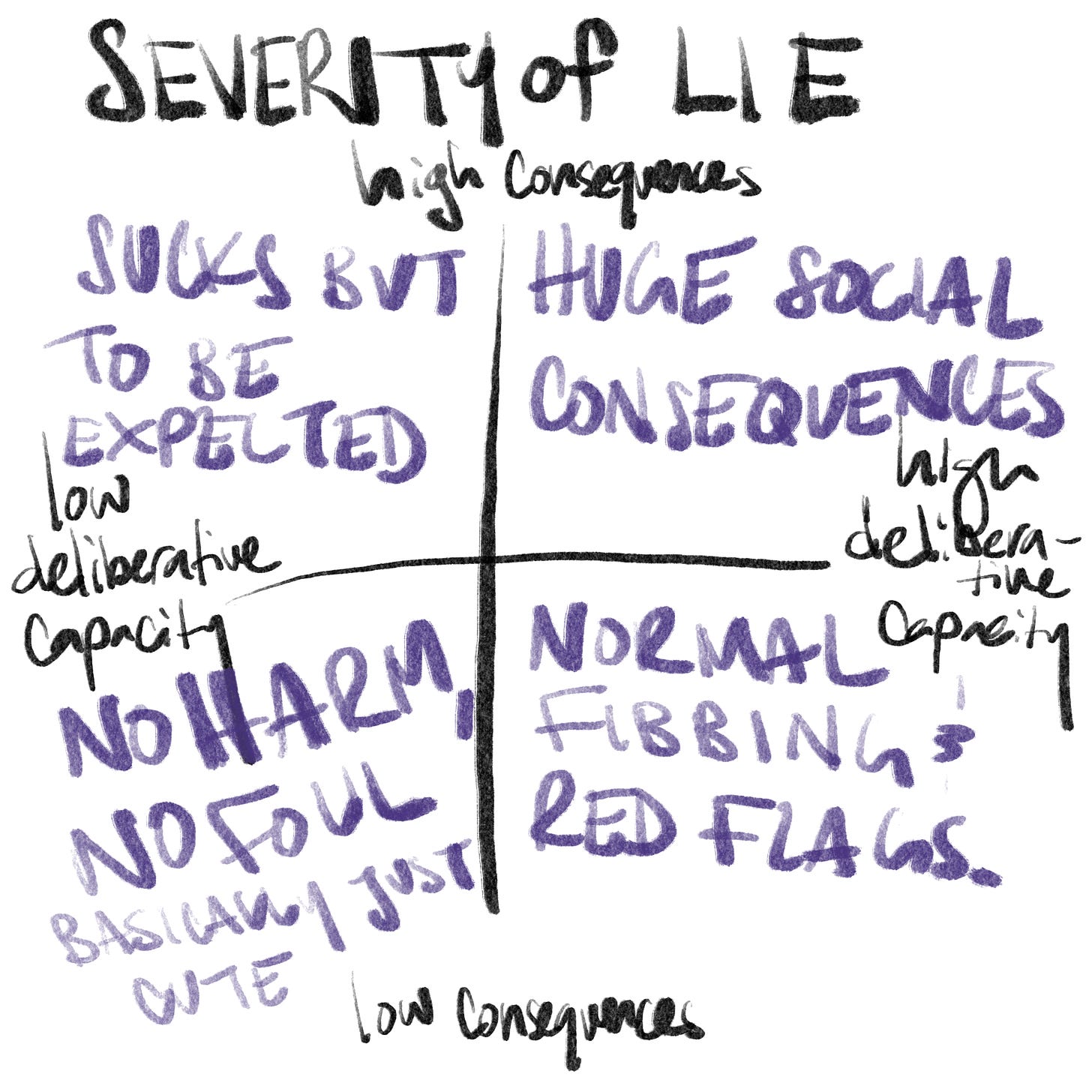

So a lie is only a lie if it’s told with the knowledge that I’m saying something not true and also the intention to deceive people. I think that this is an important distinction because I have been accused of lying a lot when I haven’t been, and because I’ve also been suspicious people were lying when they weren’t. Even in instances of genuine intentional deception, I’d say there’s another cartesian plane graph I can make, where y is “consequences” and x is something about the decision-making capacities of the person who is lying, or like “deliberative capacity:”

A child has low deliberative capacity. A child who tells a lie on purpose for which there are massive consequences is, due to literally being just a kid, definitionally less blameworthy than an adult. It would be totally unconscionable to expect a child to be “trustworthy” in the same way an adult is, because that would be asking too much of the kid. You’re going to get kids who lie more and kids who lie less, because kids are different. We don’t “trust” children the same way we trust adults, because that’s way too much pressure to put on a kid. Kids lie sometimes, and they might lie even after they have learned what lying is and when they know they’re not supposed to do it. Sometimes, those lies have big consequences, but since kids also don’t have the higher reasoning capacities or life experience to understand what consequences really are, this should be an expected occupational hazard for a parent, and a big Parenting Moment opportunity.

I’d say that there are also adults who functionally cannot be “trustworthy” through no fault of their own — if they have, for example, some kind of neuro-developmental disorder that makes it impossible for them to understand consequences completely, feel or understand empathy, or both. I’d also say it’s true if someone has grown up in such incredibly abusive circumstances that no reasonable person could expect them to know right from wrong (which actually doesn’t happen most of the time, according to the data, which is interesting — childhood abuse increases the risk for abusive adult behaviour, but the majority of even severely abused children don’t become abusive adults. I personally think that this is because abusive adult behaviour is about a delicate interplay between environment, personal responsibility, and temperament at birth, but I am also not an expert and am literally just some guy).

I’m open to the idea that there is some grey area, here. Someone might lie on purpose because they’re in a temporary state of incredible distress, even if they wouldn’t do that kind of thing under normal circumstances, which is understandable and forgivable, especially if they ‘fess up once they’ve calmed down. People might also say things that aren’t true, about themselves and what they think or feel for example, because the truth is so threatening to their self-concept that telling the truth feels dangerous, or they might describe themselves inaccurately, because they don’t have an objective enough perspective on themselves to say the truth. This might invite discernment about the capacity level that person has for reasonable adult “trustworthiness,” but I also don’t think it indicates that a feature of that person’s personality is being super comfortable being deceptive on purpose. I think there’s also the question of whether someone lies to benefit themselves, directly, or to benefit other people, where a public-spirited lie might carry less moral weight than a self-interested one. What I mean, though, is that a self-interested, intentional lie, told by a person who could reasonably be expected to know these things have consequences, and where there are consequences, amounts for a small minority of intentional lies, which is itself a minority of people saying shit that isn’t true.

People tell lies all the time for a lot of reasons, and those reasons are rarely that the person who is lying is evil. I’ve read that the average person tells four lies a day, with men lying about twice as much as women do, but the actual data is probably more complicated than that, with data sets frequently skewed by a minority of people who tend to lie a lot more than the average person. Of the lies told, very few are lies of consequence, or lies that could negatively impact another person significantly, positively impact the liar in a serious way, et cetera.

I don’t like lying. I’m bad at doing it, I’m sincerely not smart or well-organized enough to keep track of all the things I say, every lie I’ve ever told has had unintended consequences harder than just telling the truth, and it makes me feel icky, because as uncool as it is I am a moral realist and I genuinely think there’s a moral quality to undermining the social contract like that. Being lied to makes me feel helpless, disrespected, and like I can’t make well-informed decisions, which are all circumstances I rather avoid so strongly that I usually end relationships with people I can’t rely on to communicate honestly.

If I hang out with someone long enough they will eventually do something I don’t like. Usually, when someone does something I don’t like, it’s not the first time they’ve done something “wrong,” in the broadest sense of the word — it’s just the first time they’ve done something I have a hard time squaring with how I think about “good people,” or which negatively affects me in a serious way. The first time I catch someone telling me a lie, directly, I probably already know they lie sometimes, beyond the inconsequential lies people tell to keep themselves safe (lying about your name or where you live to people you don’t know), lies I generally consider to be part of the normal operations of work or school (fibbing about a dental appointment for a rare instance of blowing off work to have fun), or non-self-aggrandizing truth-stretching in order to make a story better or more interesting (what an old friend once referred to as “the-fish-was-this-big-style east-coast storytelling conventions.”) By the time the person lies to me, I’ve usually seen them tell lies that are of consequence, and which I don’t really approve of, to someone else who is not me.

I’m at a point in my life where I’m re-assessing what kind of meaning I make out of noticing people I like are often people who lie a significant amount of the time. I don’t want to be unreasonable in my expectations of others, I tend to think inconsequential fibbing is harmless and normal, and even when I notice somebody lying in a relatively consequential way, I usually err on the side of being forgiving. Pobody’s nerfect, right? It’s not reasonable or practical to dispose of every relationship in which someone behaves in a way I don’t like, repair is a useful practice, forgiveness is necessary for healthy long-term relationships.

There’s even a kind of thrill I get when someone lies, but is not lying to me, and then comes to me to be like, “ohmigod, I just told the biggest lie, I feel so awkward about it and I have to tell someone I trust — ” Transgressive behaviour is great for social bonding. The person proves to me that they are imperfect, which I hope means they will be understanding of my imperfections, and then I get to demonstrate a different kind of trustworthiness by offering them grace and understanding when they’re in a vulnerable position. Admitting to the lie preserves our relationship as a trusting, honest one, and I’m able to assume they’ll be honest with me when it really matters.

Here’s another thing, though: I’ve ended up in a lot of very loving, close relationships with dishonest and highly manipulative people. They were all genuine expressions of love and desire and I do not regret them. Also, I think I have learned what I need to, and am kind of over it. I’m assessing what kind of behaviour I want to continue to tolerate and what I do not. I think about the number of times I’ve brushed it off when somebody tells me something I know isn’t true, even if there were no real consequences — I knew it was a lie, I didn’t let the lie effect my understanding of the truth, pobody’s nerfect et cetera. I usually remain friends with the person — and, just as usually, eventually fall out with them, for reasons that usually have to do with their not being very trustworthy.

Human beings have a negative bias. We tend to focus on negative facts, for the simple reason that negative information is more salient than positive information. If I had a nice day where I went out for brunch and took a walk in the park, and then also I shit my pants in the middle of Costco, I am probably going to refer to it as “the day I shit my pants in Costco,” report it as such to my friends and doctor and so on. The rest of the information is simply not very important. If an adult of sound mind is generally trustworthy, but has been caught in at least one massive lie that had major consequences, it’s simply a function of human cognition that they’re going to have a hard time getting people to trust them after that. I also think that once we’ve had at least one person totally screw us over by lying on purpose, it’s normal more easily assume or at least suspect that every other instance of a person saying shit that’s not true is an instance of that person telling a lie on purpose. If we’ve experienced a lot of really negative effects from someone doing something that is contrary to the social contract, it’s easy to assign a lot of moral weight to lying, even if basically everyone does it, including you.

I don’t mean to be like, everyone start lying with wild abandon. What I mean is that I have found that it’s useful to interrogate my desire to decide that every instance of someone saying shit that’s not true is an instance of them intentionally deceiving me. I think that this is true even if the communication problem had serious consequences. Everybody lies. I’d like to think that this means we can ask ourselves if something someone is saying is true, without feeling like we’re also asking ourselves if they’re all the way untrustworthy, or morally bad, or whatever. Lowering the stakes about what lying means, morally, might actually help us make more accurate assessments about what’s true and what’s not. I’ve heard so many people be like, all of the evidence indicates that this person is not telling the truth, but I don’t want to insinuate they’re “a liar” — because being “a liar” and being “a bad person” are often bundled into the same messy cognitive jumble. We should be able to critically ask is this true, even just silently to ourselves, without also assuming that the answer dictates the be-all end-all of that person’s moral calibre. I have another article I have to finish about this, but I’ve often been in situations where I’ve had to be, like, I know what you’re saying isn’t true, and the person is like, how dare you tell me I am bad. And it’s like — I never said you were bad. I just said you were lying, a thing that everyone does, because that’s true.