it means 'fear of God'

Theophobia is playing a gig in New York this weekend. You should go. Here's how I know.

Theophobia plays Union Pool at 484 Union Avenue, Brooklyn, New York, with Josephine Network and Tony & the Kiki, Saturday October 21st, 2023. Tickets here. You can find them on instagram, bandcamp, soundcloud, and all major streaming services (I think). Matt uses both he and they pronouns, and I switch between throughout this piece. Thanks to Karl Hohn and Dylan Mars Greenberg, for the interviews. Please note that this article ran for a little over 24 hours with Karl’s last name misspelled. My bad. Thanks in advance to Matt. For being a good sport.

Theophobia, fronted by songwriters Dylan Mars Greenberg and Matt Ellin, is a very silly band. Also, they are dead serious. Being serious is a very silly thing to do.

On a dying microblogging platform run by a real-life Batman villain, which I refuse to leave because of the things that are wrong with me, I see a tweet about classical literature, which insists that Dostoyevsky is not something to be read for fun, but only for its very serious contributions to the canon of serious business. A cranky academic fires back that classical literature was never written to be classical, or canon — it was written to be literature, and then it got old.

Already horny for what I’m about to say, I hit the retweet function, and write, this is an enormous impediment to people actually engaging with art beyond a frankly myopic and self-serving attempt to feel satisfied about their own intelligence.

I take a huge shuddering inhale. God, I’m so smart. I don’t even know what “myopic” means and I’m not even going to look it up. I keep going: there is no inherent divide between the goofy and the profound.

Send tweet. My body hurts, which means I need to go for a walk. I put my shoes on, and hit play on the music I’m listening to. The music I’m listening to is Theophobia.

Karl Hohn is an image on my laptop screen. Karl Hohn is a Berklee-educated musician and multimedia artist with bright eyes and a careful ease to him. Karl Hohn is one of two guitarists in Theophobia.

“The way I've been describing Theophobia,” he explains, “is that it's a comedy act embedded in a very serious band embedded in a comedy act.” He tells me this from his apartment in New York City.

“Right,” I say, making a note, in my notebook, in my apartment in Montreal.

“Like a turducken,” he says. “Where the duck is the serious part.”

“I wanted it to be a performance more than anything,” Dylan tells me, in a different interview. “I always liked dadaism, and absurdism.”

She explains that her avenue into the philosophical underpinnings of the band were visual mediums, like television and movies. In addition to being an accomplished musician, Dylan has made a staggering number of films for a person in her mid-twenties, among them the recent Sir Isengord and the Theory of the Magnificent Spinning Quanto Quasi Table, a film which is so funny that a single ill-timed sip of coffee nearly caused me serious career losses when I narrowly avoided laughing the beverage onto my laptop.

“I think anyone who sort of acted really absurd, or just didn't follow the rules of how to communicate in a conventional way, sort of became my hero,” says Dylan.

“I always felt very much like in the quote-unquote real world, I was always told that my behaviour was wrong and that my actions were wrong. So I liked this idea of, well, what if wrong was right and right was wrong. Actually, everything is the opposite. There are no rules, all of a sudden. That felt really good to me.”

At one point, in my early twenties, I re-wrote the lyrics to I Was a Teenage Anarchist by Against Me! into I Was a Teenage Absurdist, about my own foray into absurdism in my adolescence and teens. As a kid, I’d been a huge fan of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and as a young person I came to understand that I had a very powerful need for people to pay attention to me. Like many people who felt this way I became an aspiring actress. My intentions, when I re-wrote the lyrics to the Against Me! song, were largely to affirm my status as some kind of cool and fuckable person, hoping to maximize attention-getting by distancing myself from any real or perceived identity as that other kind of theatre kid — the step-ball-change kind. This was a ridiculous task, looking back on it, because it was a dorky thing to do. Also, it was a lie. I was that kind of theatre kid, too.

Absurdism was more precious to me, though. It was much more personal. Without absurdism, I would not have studied philosophy, or become a writer. I would not have survived certain events in my childhood.

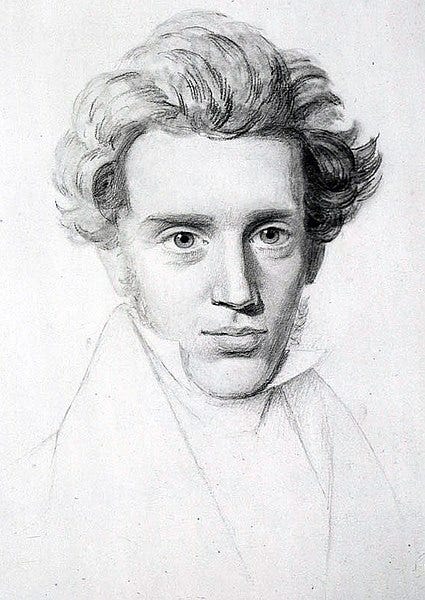

As a philosophical discipline, absurdism has its roots in the work of 19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kirkegaard, who is perhaps best known for having the hottest portrait of all of the 19th century philosophers. In addition to “a huge babe,” Kierkegaard is referred to as “the father of existentialism.” He wrote — like a poet, wise beyond his years — about the rigidity of social structures, and what it feels like to realize you don’t fit them. He wrote about the tension between wanting to fit them and not wanting to, the sense of alienation that comes with this.

He engaged with the work of Karl Marx, on this alienation piece. Where Marx came to the conclusion that this sense of alienation is imposed on working people due to the pressures of capitalist society, Kierkegaard insisted instead, alienation was the result of living too much in the world, and as such being alienated from God. Writers like Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir have since wrestled with these concepts — God and money, reason and unreason, freedom and responsibility. Whether any of this makes any sense at all — living, and being together, and making things, and not killing ourselves — especially if there is no God. What do we owe to each other? How do we find ways to be together?

Absurdism is closely related to existentialism, and even more closely related to nihilism — though it’s a bit crankier than the former, and significantly more fun at parties than the latter.

As tends to be the case with such concepts, artists got their grubby little hands on them, and began to fuck around. Theatre of the Absurd began as a post-World War II rejection of the modernist project, and realism, and the conventions of theatre more broadly. World War II had an apocalyptic effect on society and culture, on art and philosophy and the way people thought, which echoed and continues to echo. The structures of human self-concept had been violently shattered the world over. Things had been turned upside-down — right was wrong. Wrong was right. In Theatre of the Absurd, artists created something that is as fun, and compelling, and as mind-expanding and philosophically rigorous as it is highly abrasive and annoying. Because this is what theatre kids are like.

I explain to Karl that I am philosophically rigorous, highly abrasive, and annoying, because I am a theatre kid.

“Oh, me too,” he says. Somehow, I knew this. We start talking about what makes the music so compelling to people like us.

“I think that there is a connection, here,” he says, “between Dylan's filmmaking practice and her musical practice, because the songs feel like classic horror movie montage sequences. Sometimes what a narrative thread demands is not necessarily a coherent story, but a good series of images.

“I recognized immediately that [she and Matt] were really into Jim Steinman, and Jim Steinman is a Broadway guy. It's that thing where the language isn't literal, it's gestural — whether that’s verbal, or musical, or visual language.”

Dylan explains the origins of these influences, saying, “I think the first song that I made specifically for the band was God of War, that was Jim Steinman-influenced. It made me go on this really deep dive into Jim Steinman’s music, and then I forced Matt to be into it, too. And then Matt also got as insane about Jim Steinman, and we both went really crazy about Jim Steinman, and Sparks.”

I’m not a musician, but I know things about music. This is only really because I was raised primarily by my dad, due to certain events in my childhood, and my dad is a musician. Everything I know about music, I know from hanging out with him like, all the time.

I showed him the music.

“Wow.” He was quiet for a second, listening. Then: “I actually kind of can’t believe this. These are people in their twenties? It sounds just like 1970s British post-punk. This is insane.”

Sparks is an American band, but Matt described them to me as “honorary Brits.” Matt did not describe them to me this way in an interview, they described them to me this way in the living room of their Brooklyn loft, in the fading orange light of August, when I traveled to come see them the second time. While our connection had felt like getting struck by lightning, at first, I could tell that they were already closing off. I was trying not to think about it.

In the Alcoholics Anonymous meetings I’d gone to, before I quit, I had been told not to live in the imagined wreckage of the future. Albert Camus calls hope an attempt to re-capture God, and philosophical suicide. He says that once we reject it, as a concept, we are forced to surrender completely to the experience of each moment. The moment I surrendered to was one where Matt explained that Sparks were American, but honorary Brits. The sun was setting, but not gone yet. Theophobia had become my favourite band, and I was in Brooklyn with one of the songwriters. And I was in love —to my great annoyance, and against my better judgement.

I have to back up a bit.

Two months earlier, I had just turned thirty-one, and I was on an airplane from Montreal to California. I was flying to meet a woman I met on Instagram. For professional reasons, I cannot say who, or why, but I can say that it had to do with my work. This woman had found my work, on Instagram, and immediately had a gut feeling — a connection that felt like getting stuck by lightning, on which she had made the decision to invest a large amount of time and money and energy in me.

Sometimes, excellent decisions are made based on social convention, or hard data. Sometimes they are made on gut feelings. What me and my client knew about each other was that I am a writer, and she had something she needed me to write. There were people in my life who told me that I was insane for doing this, but I was happy to fly across the continent in search of glory and adventure. I always think about the adventurers who go do incredible things, and then they get asked to describe it, and then they’re like, I don’t know how to describe it, man. They should have sent a poet. I would like to be that poet. I feel like I’ll do almost anything for a good story.